How to reframe interpersonal disagreements for better outcomes

I hate conflict. My natural inclination has always been to hesitate a little too long before addressing an issue, or to rationalise to myself that a confrontation would be unproductive… you know, this time around.

(Maybe next time.)

This philosophy, particularly early in my career, proved very convenient for avoiding direct conversations. Layer on my inherent need to be liked, and it’s meant that over the years I’ve had to resist these instincts to become more assertive. The instincts never leave, though.

When I ask others to raise a hand if they have a fear or dislike of conflict, I am usually met with a sea of hands. And this fear makes sense, because welcoming any kind of conflict will bring with it an invitation for instability and a potential recalibration of interpersonal dynamics. While some might naturally be more comfortable with this than others, there are many plausible fears underlying a poor relationship with conflict. For example:

Fear that confrontation will compromise a relationship (e.g. if I bring up a work issue, it will compromise my friendship with this colleague; if I question a decision of my manager, this could strain our relationship)

Fear that the conflict will change the perception other/s have of you (e.g. being seen as someone who ‘rocks the boat’; being seen as disrespectful of existing organisational hierarchies; being seen as difficult to work with)

Fear of failure (e.g. “if my perspective has not come up, maybe that alone is a sign that it’s incorrect/not valuable?”)

Fear of loss of control that comes with the instability of conflict

Fear of violating a perceived cultural, organisational, group or relational norm

“Conflict is the beginning of consciousness”

-M. Esther Harding

Fear-inducing as it may be, interpersonal conflict is an inevitable part of being human. And it’s arguably an important part. After all, if we’re not at least occasionally placed in a position where we must engage with contrasting perspectives in an open, respectful, and critical way… then arguably we are missing out on a whole lot of opportunities to learn, grow, and contribute.

Most stories throughout history, if you were to take the conflict away, would be pretty bland. The hero’s journey upon which many narratives are based is marked by challenge, which usually involves some sort of conflict. Often, this conflict is a catalyst for transformation, character growth and story progression. In story, as in life, conflict will generate movement — though where exactly that movement will take us may be uncertain.

Some of the greatest art we have features conflict as a core theme: Chuck Palanhiuk, in a 2020 interview with Tim Ferriss, described his book Fight Club as a way for him to examine conflict, with a piece that is “all about this consensual, structured, controlled way of experiencing and exploring conflict and violence — like you would dance — that could allow everybody who had problems with conflict to kind of put their toe in the water and kind of experience conflict and develop an ability to be with it, but be less reactive to it”.

Ultimately, the ability to ‘be with’ conflict, to dance with it and to see it as an inevitable, fruitful, maybe even beautiful aspect of the human experience, is an extremely valuable skill.

Avoiding conflict: Diplomat or doormat?

What if we were all to avoid conflict altogether? If a group is hyper-conflict-averse, it runs the risk of groupthink: A phenomenon where the need for harmony dominates to a point where the group makes poor or irrational decisions. Because of this overbearing prioritisation of harmony, people are not comfortable sharing dissenting views or different perspectives within the group. They must conform. Usually, this means everyone will immediately acquiesce to the perceived leader’s opinion, or to the first idea that is raised in a group setting. This pattern builds to a point where the group starts ignoring or missing important or obvious facts, seeing itself as invincible, and behaving irrationally. (If you want a classic example of groupthink, consider the stereotypical ‘mean girls clique’.)

In a professional setting, the implications of groupthink can be as benign as perpetuating mediocrity; a group never growing or daring to venture ‘outside the box’. Or, they can be as malignant as the facilitation of an insulated, toxic culture.

While avoiding conflict may seem attractive in the short term, the language of acquiescence can also be the language of stagnation, of snotty cliques in schools, and of professional groups who are quick to exclude. In a professional setting, avoiding conflict doesn’t necessarily mean the issues go away — often, instead, they fester, growing into something much larger and harder to address.

(It is worth noting that in some cases, of course, the best possible response to potential conflict might be to avoid it: For example, if it means throwing ourselves into a battlefield when we are not well enough equipped for war, or debating for nothing more than a Snickers bar. It’s all subjective. At the same time, I do wonder if the more common issue in professional settings today is that of not addressing issues that give rise to conflict, more so than initiating conflict recklessly or too often…)

Embracing Generative Conflict

While it maintains a stereotype for being destructive, we actually engage with conflict in positive ways all the time. Productive conflict looks like a group or pair engaged in an open evaluation of ideas. It looks like individuals self-aware enough to recognise that they could be wrong; that other perspectives are valuable; and that the best outcomes appear by working through the issue rather than glossing over it. It looks like debating over attacking. Like listening over interrupting. Generative conflict looks like better idea generation; deeper understandings of each other; stronger connections; and more thoughtful resolutions.

It also brings to mind Socrates’ now-famous method of engaging with an interlocuter in a dialectic. Socrates, rather than being aggressive about his own point of view, would often rely on asking the other party thoughtful questions to prompt them to consider different perspectives. Even though he had strong opinions, he engaged in dialogue over monologue and worked with the other party, rather than against them.

A small meaningful action: Reframing conflict for better outcomes

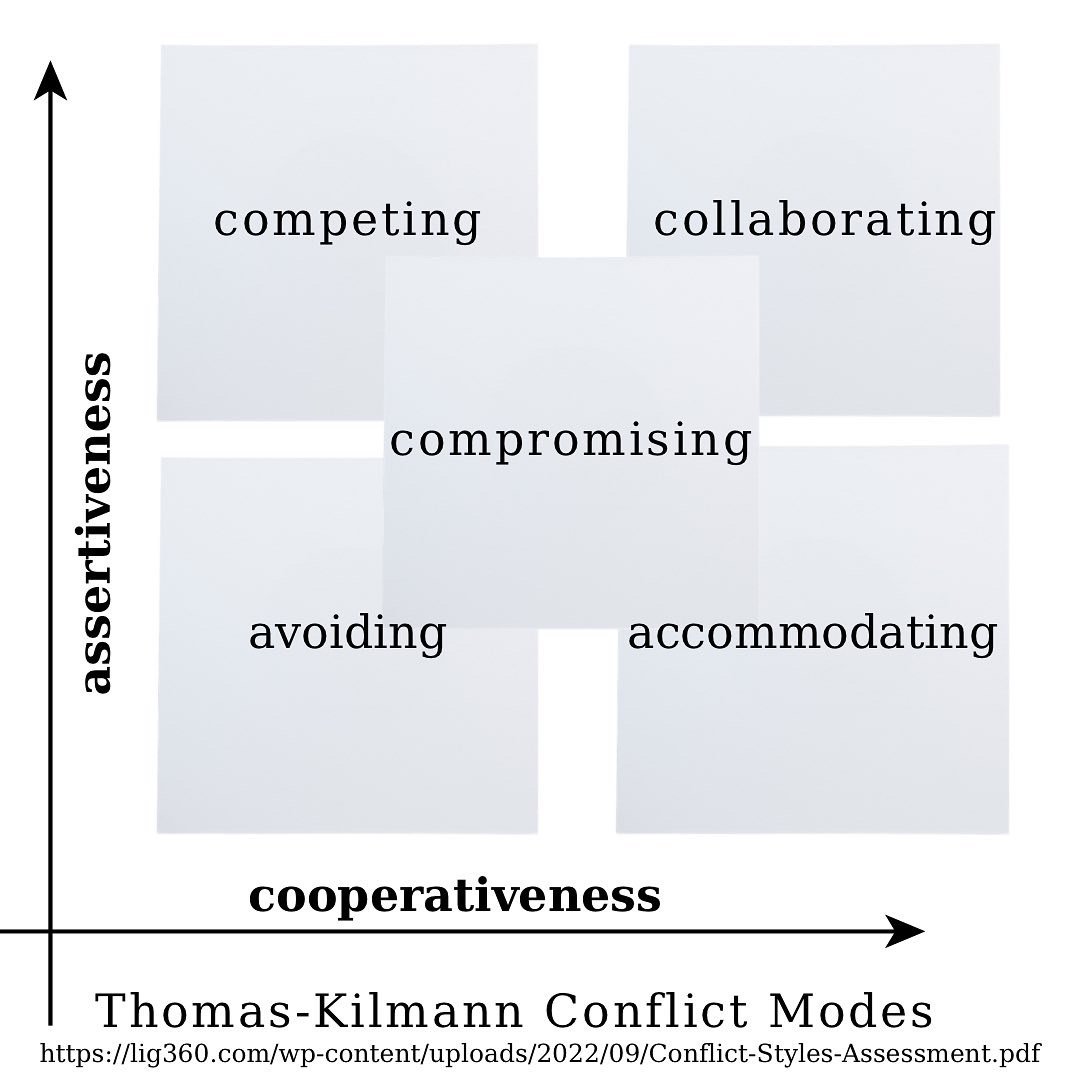

How we might reframe conflict to foster a better relationship with it depends on how we have framed conflict in the first place. It’s helpful to first reflect on what your natural approach to conflict tends to be (if you’re unsure, the Thomas Kilmann conflict modes are a great starting resource). As with most behavioural patterns, of course, our natural approach will bring its own strengths and drawbacks, so it’s worth engaging with behavioural flexibility as the situation warrants.

Regardless of your natural inclination, if, like me, you and conflict have a complex relationship, then the next time a potential disagreement is on the horizon perhaps you could experiment with some reframes to disrupt your go-to thought pattern:

Conflict as giving: From the perspective of the other party, what will they be gaining if I choose to engage in respectful conflict about this? Alternatively, am I doing a disservice to the other party by not addressing this matter? Just as research suggests that women tend to negotiate more effectively when doing so on behalf of someone else, I suggest that this reframe works in a similar way. By repositioning the potential discussion to emphasise how it will be beneficial for the other party, those of us who fear compromising relationships can shift to a perspective that recognises how conflict can enrich and serve our dynamics with others.

Conflict as learning: What might I learn from this? At the very least, a disagreement offers me a chance to reflect on my own perspective more deeply. At most, it’s an opportunity to evolve.

Conflict as healing: How might this process bring this person and I closer together? Could this propel us towards greater understanding and resolving our problems?

Conflict as exploration: What if the only goal here was to explore each others’ views, without judgement?

Conflict as creativity: When we bring diverse perspectives into a conversation, we also bring greater capacity for novel, interesting, and important ideas to emerge. What if this wasn’t about people, but just about ideas?

Conflict as important: Will I be sitting here, stewing on this tonight, tomorrow, a week from now? Will I be reconstructing in my mind a conversation where I could have respectfully brought up a point of dissent or difference about this issue? Would future me be proud that I engaged in this generative conflict?

Conflict as unimportant: Equally, how likely is it that this conflict will be as big a deal in real life as it is in my mind? Am I being too self-conscious?

Conflict as thoughtful and seeking a win:win: If, rather than avoiding conflict, one is more likely to plough into rough waters without much forethought, they might also be more likely to find themselves involved in too much conflict and confrontations that serve neither them nor the other party. Accordingly, this person may be served by heeding the warning from ancient Stoic Seneca: “The greatest remedy for anger is delay.” With that in mind, some thought disruptors might be, ‘Is the conflict I’m about to initiate thoughtful? Is it of value? Is a win:win possible?’

If you tried any of these, I’d love to hear how it went. And if you have any other comments or approaches that you employ to elevate your relationship with conflict, I’d love to hear from you.

Psst… enjoy this? Get the next one straight to your inbox — sign up free here!